A look back at the work of ice harvesting

Story by Jane Beathard

Before refrigerators spit out perfect rounds of ice for cold drinks and before freezers safely preserved food for long periods of time, mankind relied on ice hewn from mountain glaciers and freshwater lakes to enliven drinks and keep food fresh.

In this age of convenience, it’s hard to imagine that for thousands of years, ice was a luxury that only the rich and powerful enjoyed. But American ingenuity and hard work changed all that beginning in the 19th century.

A visual saga of how ice — simple frozen water — influenced human history and helped develop the American Midwest into an industrial power is now on display in Fremont.

“Ice for Everybody: Lake Erie and America’s Ice Harvesting Industry” was the brainchild of Nan Card, the museum’s manuscript curator.

Months of research followed as staff read all they could find on the once-flourishing business of commercial ice harvesting and borrowed harvesting artifacts from local families and museums along Lake Erie.

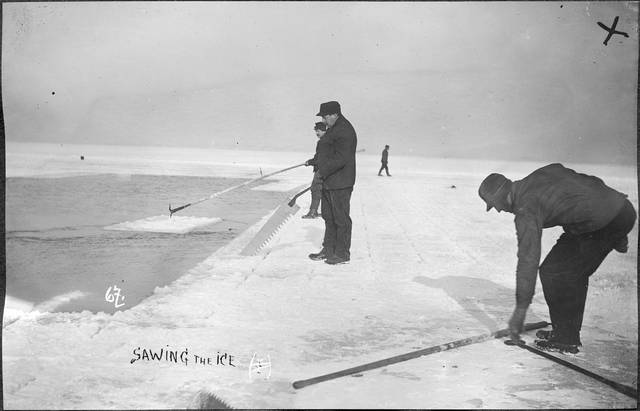

It helped that the museum is home to a collection of historic photographs by Ernst Niebergall who captured the day-to-day activities of icemen working on Lake Erie in the winter of 1911.

Those photographs, part of the museum’s Charles Frohman Collection, are an integral part of the exhibit.

They depict the way workers used horsepower to smooth and score the lake’s frozen surface, then cut that surface into 2-foot blocks that were as thick as 18 inches. Those giant “cubes” were floated or hauled to shore for storage in special warehouses and eventual transport to Midwest cities.

The work was hazardous for both men and animals. But it paid $2 per day — a good wage for those who otherwise found wintertime employment scarce. Boys who led horses onto the ice cover earned 50 to 75 cents per day.

It wasn’t that ice and its joys and benefits were unknown.

Roman emperors valued ice and commanded slaves to haul it from far-away mountains. Thomas Jefferson and George Washington also used slaves, as well as paid servants, to gather ice from their estate ponds and store it in below-ground repositories for summertime enjoyment. But it was only wealth, land and an abundance of manpower that permitted these men chilly luxuries.

In the early 1800s, an enterprising New Englander named Frederic Tudor envisioned ice as a business to benefit ordinary people. Tudor began gathering quantities of ice from frozen Eastern lakes for shipment in straw-insulated ships to the West Indies. His first ice cargos melted prematurely. But Tudor persisted and succeeded, earning the name Ice King.

But as municipal sanitation failed in Eastern cities, nearby lakes became polluted. That made ice from the Great Lakes more desirable.

Lake Erie’s shallow western basin froze quicker and deeper than other parts of the region. By the 1850s, Sandusky Bay, with its then-crystal clear water, was considered the Ice Capital of the Great Lakes. Twenty major companies pulled a frozen bounty from the bay each winter and stored it in above-ground warehouses. Those companies employed as many as 2,000 in cold months.

In 1886, a record 25 million tons of ice was harvested nationally and 400,000 tons of that came from Sandusky Bay alone. Most went by rail to Toledo and Cleveland, with some shipped as far as St. Louis. Selling price: $1 to $6 per ton, depending on the weather.

Midwest brewers, grocers and meat packers were the biggest users of Lake Erie ice. Names like Schlitz and Pabst became commonplace among those who imbibed. And Americans grew accustomed to beef and pork on their dinner tables thanks to the invention of the “ice box.”

These boxes became household staples. Ice delivery men carried 25 to 100-pound blocks into homes and slid them into the ice boxes. This early form of refrigeration kept foodstuffs fresh for a while and led Mark Twain to write in his “Life On The Mississippi” that “anybody and everybody” can now have ice.

Beginning in the 1890s, commercial harvesting declined thanks to the invention of “ice machines” that could freeze large quantities of water artificially. In 1913, the sale of the first electric refrigerator ended the need for ice as a food preservative.

Harvesting resurfaced briefly during World War I when electricity was rationed, then died permanently in the 1920s boom.

However, local fish packers continued to pull ice from Sandusky Bay until 1941.

HEAD NORTH

“Ice for Everybody: Lake Erie and America’s Ice Harvesting Industry”

Through Feb. 25

Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library & Museums

Spiegel Grove, Fremont

Visit rbhayes.org or call 419-332-4852.

__

SMALLER OPERATIONS

The Miami-Erie Canal in western Ohio was also a source of ice for food preservation and beer making in the days before electric refrigeration.

Local histories and the memories of area old timers tell of specially constructed “ice ponds” along the canal’s meandering route from Toledo to Cincinnati. Local companies, like those of Mike Hemmert and Gus Grauer in St. Marys, harvested the frozen bounty of these ponds through the 1920s and stored the ice in specially constructed warehouses (or ice houses) that were insulated with straw and sawdust.

Generally, these ice houses were located within a block or two of the canal for convenience.

One ice pond was located just south of the old paper mill in St. Marys. Grauer’s ice house was an adjoining red barn.

In Delphos, the Fisher Quarry was flooded in winter for harvesting. Several smaller ice houses appear on that city’s fire maps between 1884 and 1911.

Once a pond froze to an adequate depth, ice was sawed from the surface in 100-pound blocks. These blocks were then later re-cut into smaller lots for household distribution. That distribution came at first via horse-drawn wagon, then later by gas-powered truck.

Residents ordered ice throughout the year in 25, 50, 75 or 100-pound chunks for their home ice boxes by putting the appropriate sign in their windows.

One long-time St. Marys resident remembered that it wasn’t unusual to see neighborhood kids chasing the ice truck down the street with pocket knives, chipping off pieces for quick consumption.

The Steinle Brewery on East Second Street in Delphos had its own ice pond and ice houses. Ice harvested and stored in winter was needed to lager beer in warm months.

The Sebald ice pond was one of several outside Middletown. It provided ice for the city’s Sebald Brewery. Ice harvesting from the Sebald pond ended in 1897 when the brewery bought an ice-making machine. Prohibition ended beer production there altogether in 1919.

ID, 'source', true); $sourcelink = get_post_meta($post->ID, 'sourcelink', true); $sourcestring = '' . __('SOURCE','gabfire') . ''; if ($sourcelink != '') { echo "

$sourcestring: $source

"; } elseif ($source != '') { echo "$sourcestring: $source

"; } // Display pagination $args = array( 'before' => '' . __('Pages:','gabfire'), 'after' => '

', 'link_before' => '', 'link_after' => '', 'next_or_number' => 'number', 'nextpagelink' => __('Next page', 'gabfire'), 'previouspagelink' => __('Previous page', 'gabfire'), 'pagelink' => '%', 'echo' => 1 ); wp_link_pages($args); // Display edit post link to site admin edit_post_link(__('Edit','gabfire'),'','

'); // Post Widget gab_dynamic_sidebar('PostWidget'); ?>